The shorting of Enron back in the day triggered the major stock market crash in the U.S. in 2001. The "Doctor of Doom": today's "private credit" is similar to the subprime mortgage crisis of 2008

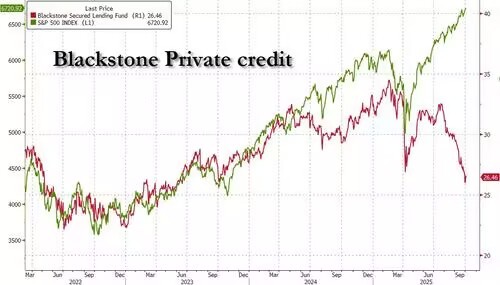

The currently booming private credit market is promising impossible "equity-like returns" for senior debt through an opaque multi-layered structure, akin to the subprime mortgages that triggered the global financial crisis in 2008

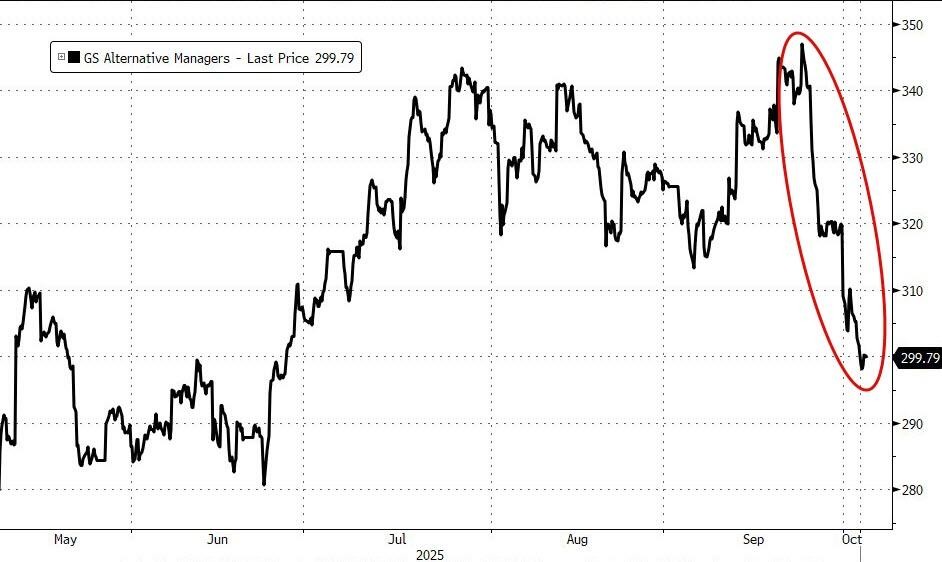

Jim Chanos, the legendary short seller on Wall Street who became famous for accurately shorting the energy giant Enron, is now focusing on a massive $2 trillion market—Private Credit.

In his view, the booming private credit market today operates in a manner similar to the subprime mortgages that triggered the global financial crisis in 2008. The biggest commonality between the two is that "there is a multi-layered structure between the source of funds and their ultimate use," and this complexity obscures the real risks.

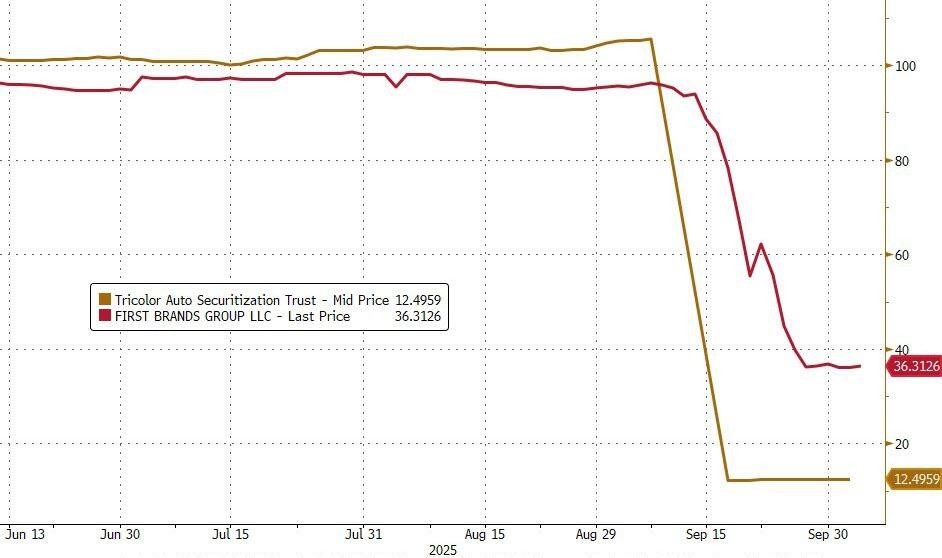

Recently, the sudden collapse of American auto parts manufacturer First Brands Group, along with its nearly $12 billion complex debt exposure, may be the "first thunder" before this potential storm arrives.

The Truth Behind the "Magic Machine": The "First Dangerous Signal" Under High Yields

In recent years, the private credit market has rapidly risen, becoming an important financing channel for companies (especially those unable or unwilling to enter the public bond market), attracting the attention of global institutional investors with its astonishing returns.

Chanos describes it as a "magic machine": institutional investors put their funds into it, taking on the risk exposure of senior debt, yet can achieve returns comparable to equity investments.

"This seemingly safe investment's high yield should itself be the first dangerous signal," Chanos stated.

He believes that these high yields do not stem from value creation but from a carefully designed complex structure. Similar to the subprime mortgage crisis of 2008, risks are hidden within the "multi-layered structure between the source and use of funds." Funds are packaged and transferred through layers, with multiple intermediaries separating the ultimate lender from the actual borrower, making the real risks of the underlying assets unclear.

A compelling example is that, according to industry-related media reports, some private credit fund managers had optimistically expected returns of over 50% on First Brands' supposedly relatively safe secured inventory debt.

Such unusually high returns precisely suggest the enormous risks that have not been fully disclosed behind them. Chanos believes that as the credit cycle reverses, similar issues to First Brands will become more apparent when the economy recedes:

"I suspect that as the economic cycle ultimately reverses, we will see more situations like 'First Brands' emerge.

Especially since private credit has added another layer of separation between borrowers and lenders."

The "Black Box" Unveiled by the First Brands Bankruptcy Case

If Chanos's warnings remain at the macro level, then the bankruptcy of First Brands provides a micro sample for dissecting the risks of private credit This privately held company owned by the low-profile businessman Patrick James has revealed nearly $12 billion in massive debt and off-balance-sheet financing after filing for bankruptcy, shocking the market.

More disturbing details have emerged during the bankruptcy investigation:

- Common Ownership: The bankruptcy filings of First Brands show that its founder Patrick James controls the group and some of its off-balance-sheet SPEs through a series of limited liability companies. Chanos called this a "huge red flag."

- Collateral Doubts: The bankruptcy investigation into its complex off-balance-sheet financing is examining whether the company has engaged in multiple pledges of the same batch of notes and has found that the debt collateral may have been "commingled."

- Information Barriers: Unlike publicly traded companies, First Brands' financial statements are not publicly available. Hundreds of institutions holding its loans (such as CLO managers) can access the financial reports but must sign confidentiality agreements. This lack of transparency makes it difficult even for Wall Street's top credit experts to see the full picture. Goldman Sachs traders only disclosed to clients a few hours before First Brands filed for bankruptcy that they had just discovered signs of its high-cost borrowing, which were "hard to explain."

This scene reminded Chanos of the pinnacle of his career—shorting Enron. Similar to First Brands, Enron heavily utilized off-balance-sheet financing, and the company's collapse triggered the major stock market crash of that year.

Now, a similar script is playing out in the private credit sector, with even greater opacity. As mentioned, unlike Enron, which was a publicly traded company and had to at least disclose its financial statements, First Brands is a private company. Although hundreds of collateralized loan obligation (CLO) fund managers can access its financial documents, they must sign confidentiality agreements. This means information is strictly confined to a small circle, without broad public and market oversight.

"We rarely have the opportunity to see how the sausage is made," Chanos commented.

However, this inherent lack of transparency is key to the private credit model. The design of this model is intended to conduct more flexible and higher-risk lending activities outside of regulatory and public scrutiny, in pursuit of excess returns. Chanos summarized:

"Opacity is part of the process. It is a feature, not a bug."

As early as 2020, Chanos stated that the financial markets were in a "golden age of fraud." Now he believes this phenomenon has "only intensified."

In this vast, unregulated, and opaque market of private credit, the next "Enron" or "subprime crisis" may be quietly germinating, which clearly warrants high vigilance from all investors and regulatory agencies